This is my cancer story.

A voice pulled me from my nightmares and into reality —the worst nightmare of all. My name, it said. I stirred. Again it repeated my name, and this time I could detect a sense of urgency coupled with fear and the dryness that only comes from hours of sobbing.

Josh.

I sat bolt-upright as the realization of what had brought that voice to my childhood home smacked me in the face.

And then came a blow harder still.

“Your mom is going to expire,” my brother said.

Expire.

The detachment of that word – no doubt from his years of medical training – stung nearly as much as the statement itself.

Who talks like that?

I was nineteen, and he was talking about my mom. Mom. I know now it was his way of coping. At the time, I felt only anger.

I got out of bed and followed my brother upstairs dreading the scene I would step into.

My body hurt. My eyes hurt – the tear ducts seeing more use over the past 48 hours than the entirety of my life.

Expire.

Another of my brothers lay beside her gently stroking her hair and talking to her in a soft voice.

I moved to her opposite side and took her hand.

Her eyes looked skyward. No recognition.

She was no longer battling cancer. Cancer had won. It had ravaged her body and was now squeezing what remained in a painful embrace.

Expire.

Dinner.

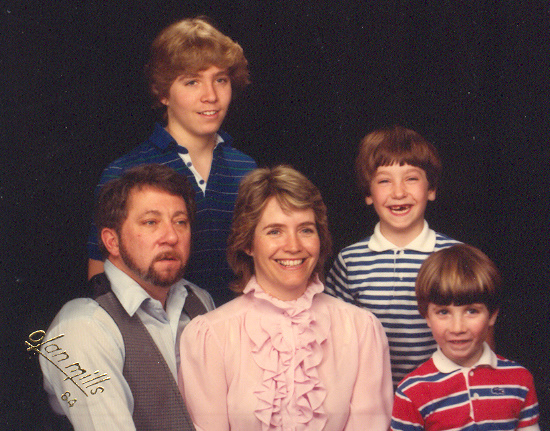

Was it last night? The night before? We had all Saturday down to dinner —Mom, my brother, his wife, Dad.

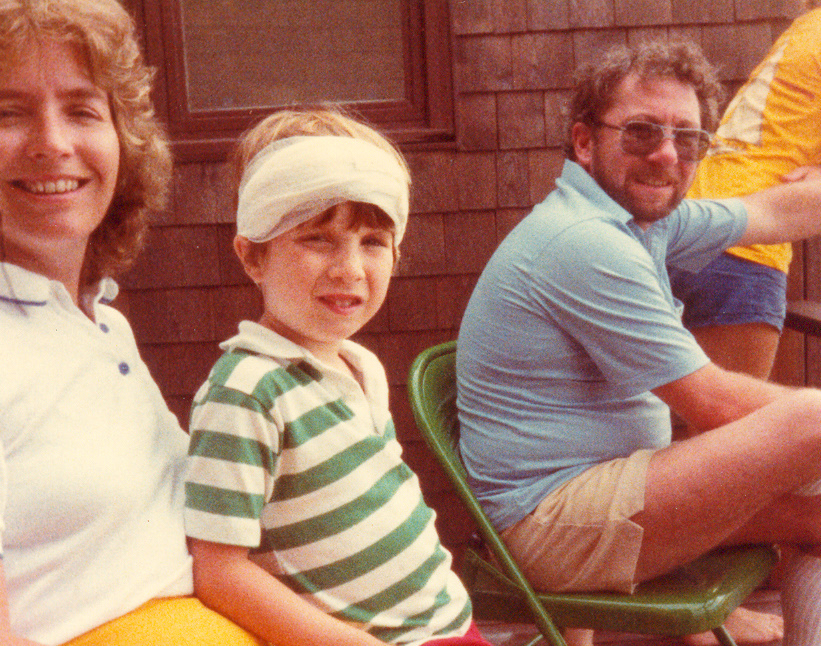

Life seemed normal. I was home from college on winter break. Days prior, my brother (2 of 5) was married. He danced with my mom at his wedding. Something I would never have the opportunity to do – although at the time I was too self-absorbed to realize it. I can’t even remember if I danced with her. God, I hope I did. My brother and his new wife were now on their honeymoon in Hawaii. 4,818 miles away

Mom didn’t eat much. She excused herself.

Later.

She was in her room. She said she hurt. She asked me what is here and here, pointing to her liver and just below. It was at that moment that my nineteen—year—old brain realized the severity of the situation. I don’t know if I did not have the heart to answer her question or if I did not know myself. I only recall not answering.

She moved to the small sofa beside the fireplace where she laid her tiny body between armrests and covered herself with a blanket. I kneeled beside her and looked into her eyes. She knew. She knew her battle had ended. She knew cancer had won. Yet, she smiled at me just like she always had —with no fear behind her eyes.

I wanted her to say something – to impart some life-changing wisdom – words to guide me in her absence, but she was silent. She leaned forward and kissed my forehead. I told her I loved her for the ten-thousandth time and she closed her eyes falling into a light sleep. I sat on the floor beside her letting the tears I’d been suppressing finally come.

In the family room, Dad was drinking – although my memories of my father during this time were ephemeral. Dad would be filling his drink, vodka tonic, pacing, staring listlessly into the distance or standing at my mother’s side. Never long as if he could escape the severity by never being still.

How can this be? He asked to no one.

My brother and his wife were talking quietly and as I stepped into the room; they took my place at my mom’s side.

I was angry at my father. He was drowning his own suffering when he should be at her side.

She was in pain.

She was dying.

She needed him more than any of us and yet he sat, unable to cope with reality.

Looking back, do I blame him? Do I still hold feelings of anger? No. Partially from a deeper understanding of their relationship and partially because I believe all people deserve forgiveness.

I did not speak to him but found isolation elsewhere and cried.

Someone had called my brother in Hawaii – they were coming home. It would take at least twelve hours and their flight didn’t depart until tomorrow afternoon, when things really took a bad turn.

Hospice was called. I didn’t know what hospice did at the time.

I walked into the master bedroom for the hundredth time to check on Mom. Her breathing was labored.

In…

Out…

She spoke very little and what she said still haunts me to this day.

It hurts.

Help me.

What could I do? I was a college kid and my dying mother was asking for my help. Take her pain away? If I had the power to absorb her pain I would have, I would have a thousand times but I did not. I held her hand, gently rubbed her short, post-chemo hair and cried like a child.

My other brothers arrived. Four out of five of us were by her side taking turns quietly talking, holding her hand, expressing our love to ears that very well may no longer be listening. The last brother, older by a mere eleven months, was in the air praying, I imagine, that he had his opportunity to say goodbye.

Darkness fell yet we paid it no heed as we each took our place by her side. Late into the night we remained as she fought to hold on. She had been told that my brother was on his way.

He will be here tomorrow.

Hold on.

I am the youngest.

The baby.

Her baby.

My childhood was time spent with my mother. When Mom and I were alone, we shared a silent bond that only introverts can understand. Being at peace with one another without feeling the need to fill the silence with words is rare. It was as if our feelings could be conveyed through silence.

She was the only person who ever babied me. Who ever let me lay my head in her lap and run her fingers through my hair while speaking soothing thoughts or not speaking at all.

I was robbed of this connection before I could ever begin to understand its power and to this day, I long for what is lost as, I imagine, do all who lose someone so close.

I stayed by her side until exhaustion took me.

Your mom is going to expire.

The urgency of her impending death never wained yet she held on. Her breathing was ragged and irregular, Her skin was pale and cold despite the blankets and fireplace. Cancer’s embrace was closing.

Hospice arrived. The nurse asked us to leave while put an adult diaper on my mom.

There is no dignity in death.

My oldest brother had left for the airport to retrieve my brother and new bride from their disrupted honeymoon. Known for his overly-cautious driving, I was later told he drove like a bat out of hell, his only concern bringing my brother home before my mother left this world.

I was at her side along with two of my brothers. My father was in and out —never one to mask his emotions, he appeared to move through stages of grief like the changing of a television channel. Tears. Anger. Acceptance. Back to anger. Denial.

How can this be? Was all I recall him saying.

Moving from the foot of her bed out to the nook where he would lose himself in the bottom of a glass while smoking incessantly and staring at a muted television screen, his mind lost in the depths of misery.

Time passed slowly. Hospice attempted to put in an IV but in her deteriorated state, finding a useable vein was impossible. The nurse ordered liquid Roxinol but the pharmacy was not yet open. Her pain would not be dulled.

The hour neared noon, the oral morphine had been administered. Mom’s breathing slowed and appeared to come with less effort. Time passed in a wave of tears and grief.

Hold on, we told her. My brother would be there soon.

It was as if she clung to that like the final thread keeping her from moving on.

Time passed. Minutes—perhaps hours. Pain. Tears. Grief. She fought, gripping that thread with every ounce of strength her failing body had left.

Hold on.

Then, he was there. My brother had arrived —his eyes red and swollen. He rushed to her side and fell to his knees as he took her hand. My father was there —we were all there —all her boys.

Mom appeared to relax.

Each of us gave her permission to let go. She had fought hard but the time for fighting had come to an end. She could be at peace.

Let go.

It is okay to go, I remember whispering in her ear —each of us did. Not long after telling her our goodbyes, she let go. Quietly, her shallow breaths stopped altogether and her heart stilled.

Cancer had won.

Eff you cancer.

In that moment my father was at his most lucid and most disconnected. No tears were shed. His voice was steady as he watched the woman he had adored for 32 years pass from this world into the next.

Our family remained by her side, some openly weeping, others in shock-induced silence. Eventually, we filed out of the room into a crowd of waiting family and friends. I remember my brother falling to his knees and crying out. I remember helping him to his feet. I remember extending my hand to greet my younger cousin and being enveloped in the first hug we ever exchanged.

My heart broke again when I looked out the window and saw Mom’s best friend hurrying up the driveway with tears streaming down her grief-stricken face. Knowing my mom’s condition, she was considering canceling a vacation but my mom insisted she go. She went and was not there in those final days. She was enjoying her life while we grieved by Mom’s side. I know Mom wouldn’t have wanted it any other way. She knew her death would be hard on her best friend and wanted nothing for her but to live and enjoy her life. The pain on her face as she walked up the driveway chiseled away at the wall I had erected to keep my own pain at bay.

Cancer took.

It stole from me the most important person in my life

—and it was not done.

The disease itself may have departed along with my mother but its impact on those left behind was just beginning.

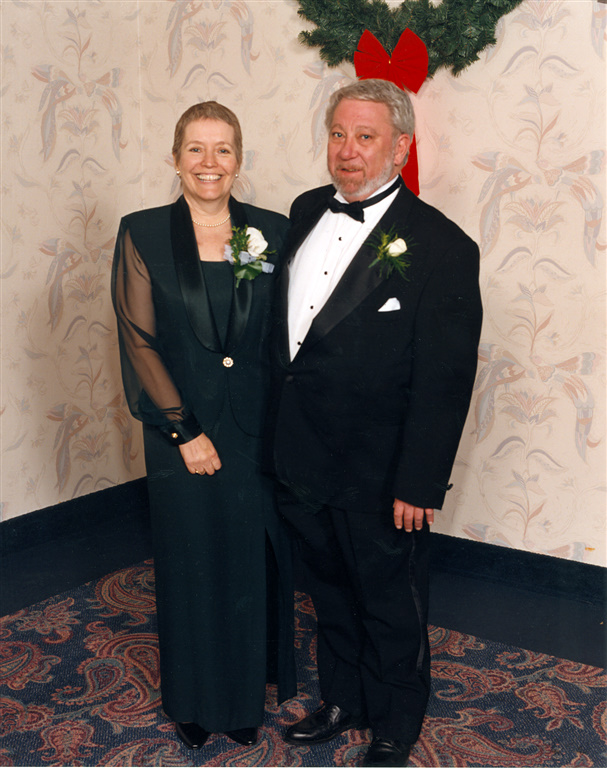

To this point in my retelling, one may view the spirit of my father as weak. Perhaps even selfish and cowardly. In truth, the man was anything but. Before cancer came for my mom, my father was a leader of men. He was respected, accomplished and seemingly fearless.

His unbridled love for my mother, his belief in the infallibility of their marriage coupled with the certainty that he would precede her in death saw to the complete and utter destruction of this man when cancer decided to lay waste to the monuments at the center of his being.

Cancer is a bomb.

It never impacts just one person. There is always collateral damage and in this case, the man standing closest was my father.

Denial held the aftermath at bay. It allowed the dust to settle and the upheaval to wane. When death comes, emptiness follows. Friends and family, ever-present the days after, return to their lives leaving in their wake a stillness. An emptiness that can consume the leftovers.

In Dad’s case. The false-front he wore fell away revealing a broken man. Shattered. Cancer never infiltrated his body but it poisoned his mind leaving a shadow of the man he once was. There were glimpses of his old self during the years after Mom died, but anyone who knew him well would tell you, he was never the same.

I was denied knowing my father —the man he was before, because of cancer.

At nineteen, I lost my mother and experienced a role reversal with my father. I believe all my brother’s felt it. We were sons who had to parent a man far too young to need parenting far too soon in our lives.

My father may have survived for another ten years but a big part of him died that same winter day alongside my mother. There is not a hint of doubt in my mind that the decline in health that eventually led to his death was directly correlated to what cancer had stolen from him.

On a warm day in January, cancer took both my parents. One physically, one mentally, and the body does not thrive without the mind so it was that in the end, cancer won two victories and left in its wake a swath of grief and emptiness that will never heal.

This is my cancer story. It is my first but not my last.

The others are not inconsequential. Not by a long shot. But my first will always be the story that echoes within me for as long as I live.

- by Josh Wagner, Team CMMD Cyclist

- Donate to support Team CMMD Cycling in the Bike-A-Thon for American Cancer Society June 12th HERE